Fans of business success stories know the familiar arc they follow:

Hero-entrepreneur dreams up a great idea, finds a sidekick or two to help it come alive, clashes with and defeats the entrenched incumbent, and rides to glory as the credits roll.

The story of Sonos might seem like that, from a distance. Its four founders – John MacFarlane, Tom Cullen, Trung Mai, and Craig Shelburne – conjured a daring vision based on technology that didn’t exist at the time. Fueled with the insight earned from success in the first phase of Internet-based business-building, they chose as their next mission a new way to bring music to every home – wirelessly, in multiple rooms, from PCs and the Internet, with awesome sound. They hired an amazing team who built amazing products from scratch, and music devotees all over the world found a new brand to fall in love with.

But what about a closer look?

What are the frustrations and failures they experienced on the journey? Are there larger lessons to be learned? The story of what Sonos did and is doing might be familiar to many. With first-ever details, what follows is the story of how.

“We had to reinvent how devices communicate with each other. We could not, and did not, limit ourselves to what existed at the time.”

The Sonos Family of multi room audio products

Part One “The View from Santa Barbara”

John MacFarlane moved to Santa Barbara in 1990 to get his Ph.D. from University of California-Santa Barbara. Instead he saw the promise of the Internet and built Software.com along with Craig, Tom and Trung. They merged Software.com with Phone.com in 2000 to create Openwave, and soon left with new, hard-earned wealth and unanswered questions about what to do next.

Whatever was going to be next, they knew they weren’t leaving Santa Barbara. The lifestyle, the ocean beaches, the weather – everything about the place compelled them to stay. It was, perhaps, the beginning of a habit of unorthodox choices to add both a degree of difficulty and a fresh perspective to the work.

As Tom describes it, the view from Santa Barbara contained four big insights drawn, in his words, from being “at the core of the Internet as it was blowing up”:

Four Big Insights

First, the proliferation of standards meant the Internet is a programmable platform.

Second, the collapse of costs for the brains and nervous systems of computers - integrated circuits, central processing units, and other technologies – meant these components were fast becoming commodities.

Third, the four founders could see what the builders were buying, and thus they could see digitization just getting started all around them, with nearly unlimited possibilities for more.

Finally, as Tom would say, they realized that for networking, “what would be large scale would become small scale.” Wide-area networks would create markets and bring reliable capability to local-area networks.

“We’ve always believed in music in every room.”

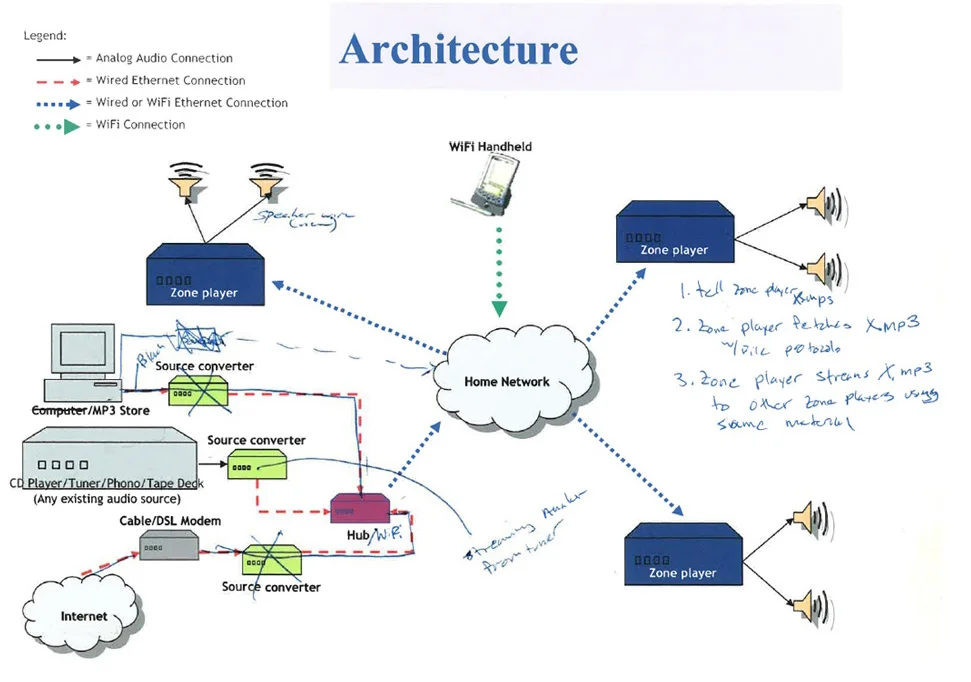

This early illustration shows the original Sonos ZP100s (now called CONNECT:AMPs) being used to bring digital music to conventional speakers.

With all of their experience, resources and insight, the four founders naturally turned to music in the home, and…

…not so fast.

John’s first pitch to his three partners was actually around aviation. The notion was an offering to enable local-area networks (or LANs) for airplanes, with passenger services provided within them. That idea did not generate the enthusiasm John had anticipated, so it was back to the drawing board.

But that drawing board soon became filled with inspiration from the four friends’ mutual love of music, and mutual frustration with the pain of storing hundreds of CDs, dealing with the tangled spaghetti of stereo and speaker wires, and enduring the expense of custom home wiring for multi-room listening experiences. This became the opportunity to apply their unique talents, resources and insight.

The vision was simple: Help music lovers play any song anywhere in their homes. The one problem, in 2002: Almost none of the necessary technology existed to achieve that. The next great startup involving music and technology would take root between the global hubs of both more than 90 miles from Los Angeles, and more than 250 miles from Silicon Valley. With a vision that was pure imagination.

Part Two“These Guys Are Kind of Nuts”

In 2002, great music in the home meant wires hidden behind bookshelves and furniture, connecting to speakers the size of bongo drums; audio jacks plugged into the right holes on the backs of receivers and players; physical media primarily in the forms of compact discs and tapes - and if you wanted a multi-room experience, an afternoon (or weekend) drilling through walls to snake wires from a central receiver to speakers throughout your home.

While the original Napster had risen and fallen as a means to find music online to play on the personal computer, digital music was still new, and the idea of streaming music directly from the Internet was far-fetched. Pandora, iTunes, Spotify, and the rest of today’s leaders in music streaming services did not exist, nor did the iPhone. The top Internet service provider in 2002 was still America Online via dial-up, and fewer than 16 million U.S. households had high-speed broadband.

Undaunted, the founders went to work scoping out their vision and seeking uniquely great talent to join them. Their first step was to translate what they imagined onto paper. According to Cullen, it took about three months and looked like this:

This very basic sketch, though updated and enhanced in multiple directions, remains part of the foundation of Sonos products today.

The second step - recruiting singular talent – took about as long. By spring 2003, the core of Sonos’ engineering and design team would be in place. Among the first in the door: Jonathan Lang (a Ph.D. in networking with a background in startups), Andy Schulert and Nick Millington (veterans of Microsoft and startups, with deep coding skills), and globally renowned product designers Mieko Kusano and Rob Lambourne, both from Philips.

Schulert felt the same affections for Boston as the founders had for Santa Barbara, Sonos opened its second office in Cambridge – with a promise to never view one office as more of a headquarters than the other.

It’s worth asking how a no-name, long-shot company like Sonos could attract such world-class talent. Along with their earlier success with Software.com, the founders had a few big advantages: a reputation for technical expertise, an extensive network of great executives, engineers and designers, an eye for talent – and a bold vision that inspired the daring.

“The question was, distributed intelligence or central intelligence? We chose distributed, not because it was easier – it wasn’t! – but because it was the right architecture for the experience we wanted to deliver.”

This intrepid band went to work, holing up together in a large open room above the Santa Barbara restaurant El Paseo, with the afternoon smell of tortillas deep frying to make chips. The beginnings were not auspicious.

“The room was arranged like a school classroom, with rows of desks and John at the teacher’s desk, elevated,” recalled Nick Millington. “He’d be working on a prototype amplifier, testing it with sine waves, which was annoying. I was trying to get the audio transport layer developed, and it kept not working and making horrible noises, right in front of the CEO watching me work all day. So I invested in headphones.”

While the challenge of inventing a multi-room wireless home audio system might have been enough, the team also collectively had made bright-line decisions around ease of use – meaning setup would have to be fast and intuitive for anyone, it would have to integrate well with any technology or service, and it would have to deliver superior sound in any home environment.

The sum of all those noble user-oriented decisions is that technical problems threatened to overwhelm the small Sonos band of engineers and designers right from the start. Cross-technology integration meant choosing Linux as the technology platform, but no drivers existed at the time for audio, for controllers’ remote buttons or scroll wheels, or for the networking that was needed. The Sonos team had to build them.

Early Sonos ads: The bolder the claims, the less copy required.

Great multi-room music meant inventing a method to get audio instantly and wirelessly to multiple speakers without listeners noticing any gaps, ever. The team faced a choice: allow each speaker to go fetch music independently, or have a master speaker fetch and distribute.

As Jonathan Lang elaborates, “The question was, distributed intelligence or central intelligence? We chose distributed, not because it was easier – it wasn’t! – but because it was the right architecture for the experience we wanted to deliver.”

The team chose the latter as the best experience for the user, but that choice had its own domino effect: how (in 2003) do you manage buffering to guard against network interruption (which would stop music mid-song), and what happens if the user removes the master speaker from the group?

In what ultimately became one of Sonos’ key patented technologies, the team customized a process called delegation expressly for multi-room, wireless music to enable transition for any and all speakers without any drop-offs. Along with a novel approach to time-stamping the digital bits of music playing via audio packets, they made it virtually impossible for a Sonos system to play music out of synch – and easy for users to link and unlink rooms, and to fling music to and from any room in the home.

“There was a lot of FUD then that it was impossible,” recalls Nick Millington. “I basically started trying stuff, prototyping on PCs – just relying on judgment tests rather than academic tests.”

“We had to reinvent how devices communicate with each other. We could not, and did not, limit ourselves to what existed at the time.”

And soon, one problem was solved. But only on PCs hooked up to each other as nodes in a network, because Sonos still had to craft its own hardware – and the PCs were wired together, because the team was struggling with the wireless part. MacFarlane was encouraging, but also unyielding: the system had to work over WiFi.

In Jonathan Lang’s words, this meant “we had to reinvent how devices communicate with each other. We could not, and did not, limit ourselves to what existed at the time.”

The team recognized mesh networking as the key. By 2003, it was a concept that had seen use in highly mobile environments, like battlefields, but never applied in the home or to the stringent demands of music experience. To develop and implement, Sonos had two choices: an easier engineering solution at the expense of its ideal user experience, or making it simple and great for users and excruciatingly difficult for its engineers.

True to form, Sonos chose the latter. Speaking of the engineering team, Mieko Kusano observed, “These guys are kind of nuts. The harder the problem gets, the more intrigued they are to solve it.”

Lang explained why: “The alternative approach to networking would have been to use others’ access points. We were convinced that would lead to a bad user experience – for example, someone in the house hitting ‘print’ would stop the music. Which would be awful.”

Tom Cullen gives Bill Gates one of the first public demos of Sonos’ ZP100 and CR100 at CES in January 2005.

The team dug in to add mesh networking capability along with the rest of its advances, and by September 2003, it was time to show John and the rest of the leadership team a prototype. As with most prototypes, some parts worked perfectly, some showed promise, and some parts flunked. The mesh network capability showed up as especially incapable.

“Keep in mind that the notion of mesh networking existed, but not in any audio products. Almost no one anywhere was working on embedded systems with WiFi. There were no good Linux drivers with WiFi. We were building our own hardware that we hadn’t fully tested. Nick’s the best developer I’ve ever worked with, by far.”

Sonos turned to Nick Millington, who had already established himself among his colleagues as an elite developer with his inventions in audio synch. It didn’t matter, either to him or to the rest of the team, that he brought exactly zero experience in networking to the assignment. With the help of faculty at UC-Santa Barbara, a consultant, and a vendor, Nick taught himself in six weeks about mesh networks while also building one from scratch for Sonos – on hardware Sonos was also designing from scratch.

His manager at the time, Andy Schulert, remembers: “Keep in mind that the notion of mesh networking existed, but not in any audio products. Almost no one anywhere was working on embedded systems with WiFi. There were no good Linux drivers with WiFi. We were building our own hardware that we hadn’t fully tested. Nick’s the best developer I’ve ever worked with, by far.”

In the meantime, Rob Lambourne and Mieko Kusano were leading the effort to write product specs, develop wireframes, test with user groups toward creating the right user experience presented in beautifully designed hardware.

With the basic framework of the system built by early 2004, filled with new and untested technologies, the next phase focused on the scourge of software engineers: bugs.

“We’ve got our first 15 to 20 prototypes, we feel great about them, we take ten of them to someone’s house to try it out. We set them up, and it’s a colossal failure. They barely worked. We had to dial back to just two, figure out the issues, then add a third, and so on. Excruciating, but worth it.”

Despite all the ingenuity at hand, the prototypes couldn’t communicate wirelessly to each other from even ten feet apart. And particularly with embedded systems, at the time developer tools and debuggers did not exist.

So Nick and John took a road trip, the prototypes stowed in a cardboard box in the back seat of John’s car, to Silicon Valley to see John’s friend and hardware supplier, whose advice boiled down to one word: antennas.

This led to another round of grinding through arcane technical details around transmission standards (only 802.11-b/g at the time), antenna selection and placement, network device drivers and spanning tree protocols, and the many ways human living spaces can cause signal interference. This was a time that none of the principals describe with any romanticism or even nostalgia: it was simply a lot of work, day after day, with incremental progress instead of eureka moments or big breakthroughs.

Developers know that the most frustrating bugs are the so-called “irreproducible” bugs. Many of them emerged from testing at Sonos employee homes in and around Santa Barbara – including one especially frustrating bug, only reproducible at one person’s house, that required a packet sniffer to identify and fix.

Sonos’ first product, the ZP100, earned praise for simple set-up, ease-of-use, great sound.

Recalls Andy Schulert: “We’ve got our first 15 to 20 prototypes, we feel great about them, we take ten of them to someone’s house to try it out. We set them up, and it’s a colossal failure. They barely worked. We had to dial back to just two, figure out the issues, then add a third, and so on. Excruciating, but worth it.”

“I was responsible for capturing and protecting all the early intellectual property, and I firmly believed we were making the right design choices. But at the same time, every once in a while we’d raise our heads up from our work, realize we were all alone, and wonder ‘how come no one else is doing it’?”

By summer 2004, Sonos had tackled the bugs, prototypes were beginning to function with the necessary reliability, and the team had started sneak-peeking the system to others in the industry. This confirmed what they had been beginning to recognize: the hard work to that point had paid off in the form of something genuinely new.

As Jonathan Lang explains, “I was responsible for capturing and protecting all the early intellectual property, and I firmly believed we were making the right design choices. But at the same time, every once in a while we’d raise our heads up from our work, realize we were all alone, and wonder ‘how come no one else is doing it’?”

The industry reaction along the way was electric, featuring a demo at the 2004 D: All Things Digital conference that put Sonos on the map. As the late Steve Jobs was unveiling Apple’s Airport Express on the main stage as its solution for home audio – one that required users to return to their computers to control the music - Sonos was in one of the hallways demonstrating more advanced functionality and full user control in the palm of the hand.

Breakthrough music experiences often debut with certain signature songs. MTV, for example, famously launched with “Video Killed the Radio Star,” by The Buggles. How about Sonos? The first song played for the public on Sonos’ first product, the ZP100, was The Beastie Boys’ “No Sleep ‘Til Brooklyn,” at full volume, produced by longtime Sonos supporter/adviser Rick Rubin.

Sonos engineers could affirm the “no sleep” part because of all the work they’d put in leading up to the ZP100’s launch. But getting the experience just right for customers required a more practical approach to selecting songs for testing, dictated by the early days of scrolling through long alphabetical-order lists of songs and bands.

So the most-played song by Sonos engineers for testing was “3AM” by Matchbox 20, for no other reason than it was at the top of a list. The most-played band: 10,000 Maniacs.

Mieko Kusano recalls another encounter that summed it up:

“Among the first outsiders to see our early zone players were a team of engineers and executives from a well-known consumer technology company. It was our first meeting with this company, and it was before our launch. We had our Zone Players up and running, our controllers up and running – and one of their guys took our controller and bolted from the conference room. Totally took us by surprise. A few minutes later, he comes back with the controller, all out of breath. He’d taken it all the way out to the parking lot to see if it would still work. And it did.”

The early industry encouragement didn’t mean they were free from new setbacks. Sonos had committed to a fall 2004 ship schedule for its first products, and co-founder Trung Mai had spent most of 2004 hopscotching across Asia with foam models of the hardware to find the right contract manufacturer. Once secured, Jonathan Lang jumped in and took over responsibility for overseeing the factory lines – another career first for him. As the product lines were rolling, he noticed what he described as a “small issue” with the controllers, specifically with a glue agent that wasn’t working right.

“I had to make a call,” he said. “But I already knew the Sonos thing to do was stop the line, scrap the products, be late, and go find a glue that worked. John and the leadership team let me make the right decision.”

Part Three “Easily the Best”

At long last, on January 27, 2005, Sonos shipped its first product, the ZP100. Industry accolades, strong product reviews, and positive media coverage followed soon after, and sustained over the first months and years of availability. Reviewers lauded its simplicity of setup, design, reliability, and great sound. The dean of product reviewers, Walt Mossberg (then at The Wall Street Journal), wrote, “The Sonos System is easily the best music streaming product I have seen and tested.”

Sonos launch the ZP100 in January of 2005 - It's a hit.

With so much positive response from the media and industry, Sonos executives thought they’d be overwhelmed by a flood of revenues. Instead, sales were decent, but not amazing. As Tom Cullen described to Fortune in a 2012 profile on the company:

“We were just sitting there going, ‘everybody loved this,’” recalls Cullen…. “Why aren't we going to $500 million [in sales] in a day?” Then, the recession hit the company hard. "The world stopped. After all, nobody needs a Sonos,” says Cullen. At the time, the company was working on a larger wireless speaker, but didn’t have the capital to follow through. Some staffers, including Cullen, borrowed money from friends and resorted to paying employees out-of-pocket [Trung Mai, in particular, did this more than once, according to Cullen].

Sonos determinedly stayed the course, making key bets on next-generation systems and technologies with conviction that consumers would catch up. The company relied on John’s instinct to anticipate trends and take advantage of them, even if it risked being too early.

Its second- and third-generation systems were efforts toward streaming direct to its players, taking the PC entirely out of the equation. They started in 2006, with Rhapsody as its first music service. It was a big turning point for the company, and it was not at all obvious at the time.

Sonos CR200 Controller

With the launch of the iPhone in 2007 and Apple’s App Store sparking a boom for apps, Sonos launched its own, free app for iPhone users, meaning you could turn your iPhone into the controller, without buying the Sonos remote. (Android users got their Sonos app in 2011, and Sonos phased out its own controller hardware in 2012.)

Then in November 2009, Sonos released the PLAY:5, a truly smart, all-in-one speaker for $400, about a third of the inaugural price of Sonos’ original product, the ZP100 (which with speakers and controller, cost about $1200 in 2005). Their hopes for sustained, strong sales growth were realized. This also marked a more decisive shift toward continual software upgrades for ongoing improvement in the products, an ever-more-exacting focus on sound quality, and closer relationships with recording artists and others in the creative community.

Sonos first generation Play:5

Those relationships took Sonos to a new dimension as a company. Sonos recognized that making music sound great in the home means asking the makers how they want their music to sound. Sonos quickly learned that, as exacting as its engineers and designers might be, there are no more demanding critics than musicians.

Sonos established early testing and feedback processes for its products with the creative community, involving producers, musicians and composers. With Trueplay, launched in 2015, producer Rick Rubin headlined a team of advisers to bring the artists’ perspective into the product development process from its beginning.

Rick explained the genesis of TruePlay when it was unveiled:

““Anytime we get new speakers in the studio, we hire a professional to come in and tune the speakers to the room. Every room sounds different, so you need someone to come in and EQ those speakers for the space. So I suggested to John, the founder of Sonos, that it would be interesting if there were a way to make that same technology available for everybody.””

Part Four “By Music Lovers. For Music Lovers.”

Sonos as a brand and company built a sturdy foundation in those first years, when its culture first took shape – one that puts the experience first, is relentlessly progressive, and one where people treat their customers as they would want to be treated. It continues to attract world-class talent looking to be pioneers, who are willing to push themselves to break new ground, within a set of principles established in 2003.

A by-product of these principles is, without hyperbole, a fanatical obsession about quality. This obsession showed itself specifically in Jonathan Lang’s decision, with Sonos leadership’s strong support, to scrap a large quantity of manufactured products and start over again because of a small bit of glue – and more generally in the long, drawn-out grind to get the first wave of products exactly right.

It shows in Mieko Kusano’s and Rob Lambourne’s conviction to build sharp design and ease-of-use from the beginning to every phase of product development, with strict attention to detail.

“User experience needs to be deep in the bones of a product, not on the skin. The right way to design is from the inside out. You don’t design a technical architecture and then make it look pretty. You start with the customer. Hone in on the key areas where you are trying to make a difference and make it special. Then it’s all hands on deck to re-invent.”

Mieko describes the approach: “User experience needs to be deep in the bones of a product, not on the skin. The right way to design is from the inside out. You don’t design a technical architecture and then make it look pretty. You start with the customer. Hone in on the key areas where you are trying to make a difference and make it special. Then it’s all hands on deck to re-invent.”

Not many companies will go to the extreme of developing a new plastic resin, which Sonos did to help eliminate vibration and improve the versatility of its subwoofers and speakers. Sonos culture means extended deliberation and testing over the size, number and placement of vent holes in the new PLAYBASE (there are 43,000 holes in the PLAYBASE, of different sizes, for anyone curious).

Sonos Playbase, Sub and Play:1s

An inseparable element of this exacting environment of creativity and precision is an unapologetic belief in protecting invention. One of Jonathan Lang’s first assignments at Sonos, irrespective of lack of experience in intellectual property, was capturing each new Sonos advance in order to protect it through patents. At Sonos, engineers and designers have maintained an enduring appreciation for IP rights as a basis for competition, industry partnership, and innovation.

Amidst all this pursuit of technical excellence, Sonos has kept its eye on its mission to fill every home with music. As Meiko Kusano says, Sonos is “By music lovers. For music lovers.”

When looking to the future, people at Sonos are clear they are not about merely constructing marvels of technology. They are crafting richer music experiences within the home, which means joining forces across the universal divide between engineering and creative talent. They have witnessed the difference it brings in the experience for musicians and listeners at home. Artists feel satisfied that their work sounds as it should. Music lovers get the joy of experiencing music together at home.

And in that way, the story concludes where it started. A group of people, in many rooms around the world, focused on a daring vision: any song, in any room, always sounding amazing.

http://www.sonos.com/en-us/sonos-innovation-history